The Shape of Things

On meeting the moment, and a brand new, exclusive to Substack poem

I wrapped my last class of the fall semester early this evening and wished my first year college students a restful break. I had visions of heading out of campus early and getting my night at home started sooner, but it’s been forty minutes since they left, and I’m still sitting here in my empty classroom, which is one of the beautiful acting and dance studios here at Emerson College.

I feel fixed to the floor. I can’t bring myself to leave, though there’s no one left to teach in this space.

In this moment, I feel a flavor of what I felt the day I tried to leave my Grandpa’s farmhouse when my family sold it back in 2021: feeling physically unable to bring myself to walk out the door, yet restless in the space. I felt fixed to the floor then, too. I couldn’t bring myself to leave. It was as if I wanted to become part of the furniture, the walls themselves, flesh and bone melting into plaster and pine and paint.

The farm and I were one. I was conceived in this house, brought back to its shelter and green fields after I was born; I learned what it meant to feel the sun here, touch my feet to the earth, and what feeling surrounded by family felt like.

How is it possible to undo our shared heartbeat, pry apart our communal lungs?

When I moved to Boston in 2010, I came for Emerson College. I began my graduate program in this building where I now sit. I had one of my first classes in this very space. I started teaching in this room in 2017.

Here I am both guide and seeker.

How is it possible to let the space stand on its own, and me leave the warmth of its walls? Beloved teachers and mentors taught me in this very room, humans who have left this earth since, and it was here that friends that have become family first gathered. Now we are scattered across the country and I struggle to imagine a time, a past reality, where we sat side by side in this room, discovering how theatre could cultivate community and ignite change.

I float between that past and this present.

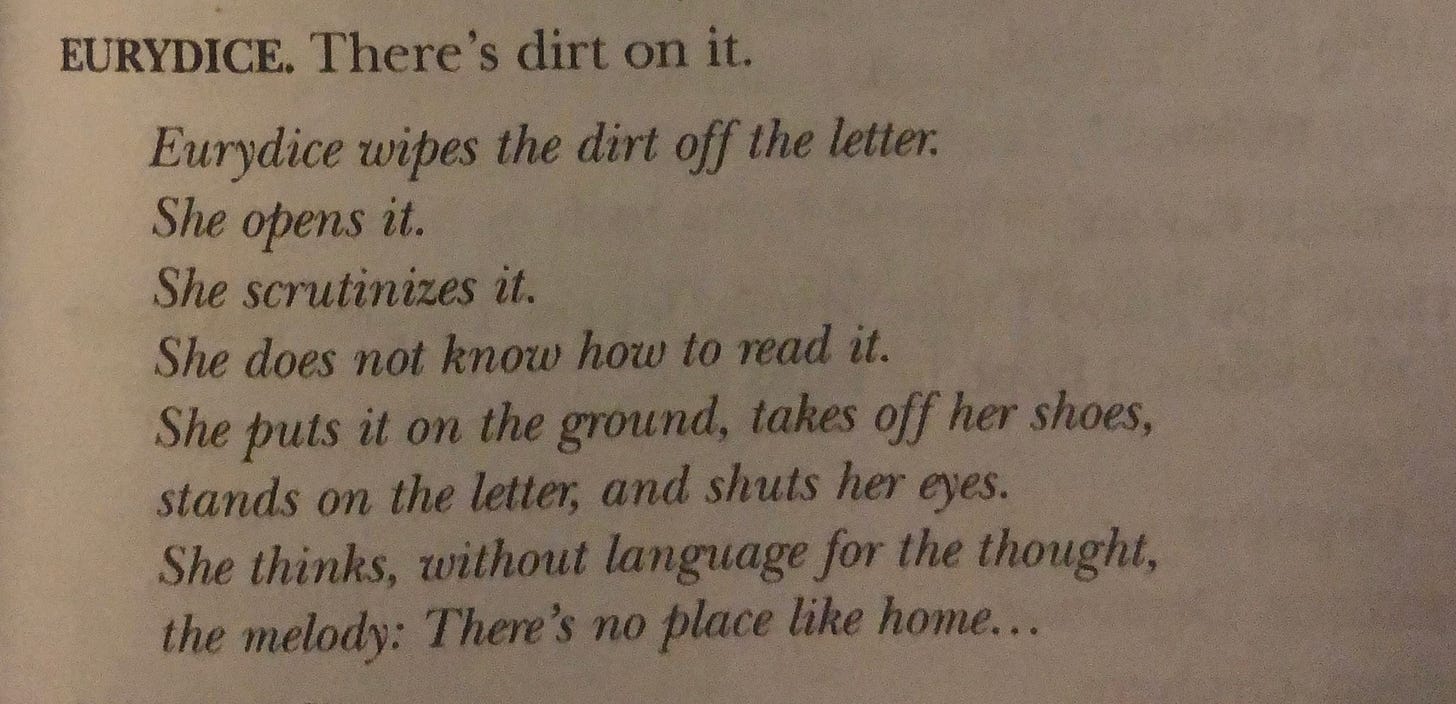

Final exams in my course this week consisted of a mock production tea, project for the play Eurydice by Sarah Ruhl. The play itself is about the pull between the past and present, both of which allow you to flex towards a future. It is a play about memory, about grief, and about what could come from one last conversation with someone you love who has passed on. My students design all the elements of a mock production of the play and present their concept in small groups; they share lighting plots, set renderings, costume designs, and posters for their theoretical production. After, each group performs a scene from the play.

Today was the last class of the semester, the last group presentation, and at the very end, the last scene. The scene the last group chose is Scene 6 from the Second Movement of the play, one between Eurydice and her Father, when she receives a letter from her husband Orpheus, whom she has forgotten in the Underworld. A letter, delivered from the Overworld to the Underworld via the soil, by a worm, makes its way to her and charges her memory.

Throughout the presentation, I had been taking notes to refer to when I grade and send feedback later this week. When the scene starts, I lay my laptop down and set my phone and pen on top of it. The ending of the scene - of this moment in time in this space - hurts. Yet, I don’t want to have any emotional crutches for this moment.

I want to be here, unadorned by anything but awe and heartbeats and the communal presence of every person in this room. I feel like I’m nearly at the top of The Jack Rabbit, the old wooden roller coaster that my Uncle Bill took me on when I was 11 or 12. I was terrified to even get in line, but once I was buckled into the seat, with no turning back, I felt delight begin to creep in. Disbelief that I could be on my way to such an adventure.

I loved being in that coaster car, clicking its way to the top of the hill before plunging over the edge of the big drop before me. It felt like I was flying. In those moments, my spirit was free. It took me time to trust that I didn’t need to cling to the safety bar in order to stay safe, and over the course of a dozen or so rides, I found enough faith to lift my hands just the tiniest bit from the bar, and open my palms, my own version of throwing my hands in the air. A posture of freedom.

Back in my classroom, watching my students perform, I’m not riding the Jack Rabbit, so I don’t throw my hands in the air for the final moments of the scene. I do, however, open my palms and place them face up on the laptop, as if to be ready to hold space for the energy that’s coursing through the air, held aloft by the words of the scene and the singular attention of us all in that moment.

I don’t want to cling to or covet this moment. I desire to be a wire, ready to allow the charge to pass through me. I can’t keep it, but I can be open and alive as it travels onward. I want to know I was here, in this moment. Dynamic and wobbly, but not getting in the way of all that is holy here.

I will miss this space, the shape of these days. What once was a dream - coming to Emerson - is now the present, and at the same time, will one day be the past. What can I do? As Tony Kushner says in Angels in America, “The world only spins forward. More life.”

Tonite, I let the wires show, just as Tony Kushner says in Angels in America that they should. “It’s OK if the wires show, and maybe it’s good that they do.” The magic, he says, comes from letting the mechanism be seen – he argues that the magic is no less real, no less lush this way. It’s magic because it’s real.

The scene is over and the spell is broken and we all applaud. I see how proud they look and I notice how proud I feel of them, of us, for showing up in this space to see and be seen.

Before the students make their way out into the world to catch rides, buses, trains, and airplanes, headed for wherever home means for them, I quote Prior in the last scene of Angels in America.

“You are fabulous creatures, each and every one of you.” And I tell them that even though I don’t have the authority in any way to bless them, I bless them. Tony helps me out again. “More life.”

“The Great Work begins.” A student speaks the rest of Prior’s line; they have picked up the cue that I never expected. “Yes, the Great Work begins,” I say.

Sitting alone in the studio after they leave, I open my palms once more, in every sense that I am able to. I often get tricked into believing that if I steel myself against the swell of fear, grief, even joy, that I won’t be taken underwater, that I will be able to maintain control. Here I am, still guide and seeker. I don’t want to stay dry in this moment. I’m willing to go out to sea.

Being human – that is, to me, being a cosmic being having a temporary physical experience here on this plane - isn’t about controlling or staying safe inside the lines; to me, being human is about surrendering to the foamy surf that threatens to take us under – for good, one of these times – with a hearty dose of faith that it will eventually wash over us and deliver us back to the shore, salt burned and scared, but still whole and made new.

If I let myself get tossed around in the swell of the grief of this moment of transition, I will cry. Why are we so scared to shed tears?

I cry in my classroom.

I feel the Fear and Sadness rise up, like a wave. That’s ok, I’m strong enough to surrender to it. I consent to go under the waves, to swim and flail and float and be part of the ocean.

Breathing, breathing, breathing.

I open my laptop and begin to type out what this feels like, to be here, to be here now. The taps of these keys slow the beating of my heart, in the best way, and I feel more grounded. I am here, crawling through, getting to see the tiny details of the heart close up. What a dark, brilliant, messy gift, and just in time for Christmas.

It feels like a long time since my students left the room, yet the energy of our community stays in the air, like perfume, and I feel the sadness still sloshing in my heart, but braided together with a deep well of gratitude and wonder that I get to have this experience at all. The sloshing will continue long after I leave this room and ride the subway home, but I won’t need an ark to survive it. My body is the boat and I’m choosing to hear the lapping and slapping of the sea as a lullaby that I can trust will always carry me home, if I let it.

I’ll sing to the sadness that comes through me, and it in turn will rock me, and together we will go on to live a new day. I’m not running anymore. I will be with it, always, and it will be with me. These days, we keep each other company.

In the spirit of giving a shape to experience, I’m leaving you with a poem about what dancing with fear feels like, in the form of a pantoum, a Malaysian form that I experimented with earlier this fall. May you trust there is a shape to whatever it is that’s visiting you at the moment, Friends.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Perpetual Visitor to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.